Message for the Sixteenth Sunday after Pentecost, Year A (9/17/2023)

Psalm 103:8-13

Matthew 18:21-23

I suspect Peter thinks he’s being gracious when he asks his question in today’s episode from Matthew: “Lord, if [my sibling] sins against me, how often should I forgive? As many as seven times?” It would seem that seven times is more than enough. That covers three strikes times two, plus a bonus chance. But, Jesus sees through Peter’s question to what he really means: Lord, when can I stop forgiving?[1] How much is too much? “Not seven times,” Jesus replies, “but, I tell you, seventy-seven times.” An alternate translation has that number at seventy times seven, or four hundred ninety: “Not seven times, but, I tell you, four hundred ninety times.” Either way, the point is clear: Stop keeping score, Peter.[2] Forgiveness has no limits.

In other words, forgiveness isn’t a system of accounting, but a way of life. It’s an ongoing practice of responding to God’s own limitless grace. “LORD, you are full of compassion and mercy,” the psalmist sings,

slow to anger and abounding in steadfast love…. You have not dealt with us according to our sins, nor repaid us according to our iniquities…. As far as the east is from the west, so far have you removed our transgressions from us. As a father has compassion for his children, so you have compassion for those who fear you, O LORD.

And, the grace of God is life-changing. That’s the key to understanding Jesus’ troubling parable in our Gospel today. By forgiving a fantastically large debt, the king sets in motion a cycle of liberation for all his subjects– grace should engender more grace, ultimately freeing everyone from debt. But, the direct beneficiary of the king’s mercy breaks the cycle, refusing to extend that same mercy to his fellow subject. His imprisonment, therefore, represents a natural consequence. He receives grace, but he’s not transformed by it.[3] That is to say, he immediately reverts to a merciless, debt-ridden system; he elects to continue keeping score, which is itself a kind of captivity.

Since God’s mercy is measureless, constant,[4] inexhaustible, our own outlook on forgiveness is correspondingly expansive. It’s not a matter of calculation, but of grace and gratitude. We are “already and always forgiven,”[5] so we look upon others, even our offenders, with the eyes of Jesus, who pleads with God to forgive his own murderers: “Father, forgive them; for they do not know not what they are doing.”[6]

The cycle of grace also breaks down, however, in the absence of accountability. It’s often the case that disempowered people are required to forgive powerful offenders according to what Isabel Wilkerson calls a “one-sided contract between the subordinate and the dominant.” She points to this dynamic, for instance, in the history of American racism, quoting Roxane Gay:

Black people forgive because we need to survive. We have to forgive time and time again while racism or white silence in the face of racism continues to thrive…. We forgive and forgive and forgive and those who trespass against us continue to trespass against us.[7]

Mercy has to have teeth; grace has to be efficacious, otherwise it’s just a get-out-of-jail-free card. So, forgiveness and repair are two sides of the same coin; we have to see the wound and bind it up before we can expect it to heal.

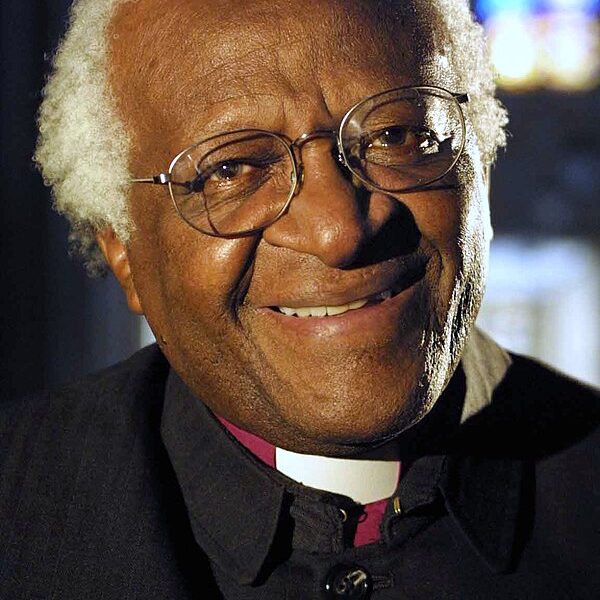

The late Archbishop Desmond Tutu was one of the world’s foremost authorities on forgiveness, serving as chair of South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission in the wake of Apartheid. He maintained that forgiveness is the only means of averting the disaster of ongoing retribution; without forgiveness there is no future. But, he was equally insistent that forgiveness depends on an unflinching assessment of the facts:

[Excerpt from The Book of Forgiving, pp.23-4]

Friends, forgiveness and confession go hand in hand; grace and truth together are what make us free.[8] And as people of faith, we rely on God alone to inspire us to that end. “Holy Spirit, Forgiving and giving,” we pray along with Hildegard of Bingen, the medieval saint whom we commemorate today, “uniting strangers, reconciling enemies, / Seeking the lost, and enfolding us together, / Fill these gathered here!”[9]

[1] See Kathryn D. Blanchard, in Feasting on the Word, Year A, Vol. 4, 68.

[2] Sundays and Seasons Day Resources for September 17th, 2023: members.sundaysandseasons.com/Home/TextsAndResources#resources.

[3] Jen Rude, Preaching Peace Tacoma Table, 9/12/2023.

[4] Karoline Lewis, www.workingpreacher.org/craft.aspx?post=4968.

[5] Confession and Forgiveness, Sundays and Seasons Day Texts for September 17th, 2023: members.sundaysandseasons.com/Home/TextsAndResources#texts.

[6] Luke 23:34.

[7] Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents, 288.

[8] John 1:14; 8:32.

[9] www.justprayer.gracespace.info/2285/.

Liturgy © 2023 Augsburg Fortress. All rights reserved. Used by permission under OneLicense # A-706920.

Liturgy © True Vine Music (TrueVinemusic.com). All rights reserved. Used by permission under CCLI license #11177466.

“Awake, O Sleeper, Rise from Death”; Text © 1980 Augsburg Publishing House, admin. Augsburg Fortress. . All rights reserved. Used by permission under OneLicense #A-706920.

“O God beyond All Praising”; text: Michael Perry, 1942-1996; music: Gustav Holst, 1874-1934; text © 1982, 1987 Jubilate Hymns, admin. Hope Publishing Company. All rights reserved. Used by permission under OneLicense #A-706920.

“Where Charity and Love Prevail”; text: Latin hymn, 9th cent.; tr. Omer Westendorf, 1916-1997, alt. © 1960 World Library Publications; music: attr. Lucius Chapin, 1760-1842. All rights reserved. Used by permission under OneLicense # A-706920.

“Loaves Were Broken Words Were Spoken”; Text © 2006 GIA Publications, Inc., giamusic.com. All rights reserved.

Music © 1987 GIA Publications, Inc., giamusic.com. All rights reserved.

“Praise the Lord, Rise Up Rejoicing”; text: Howard C. A. Gaunt, 1902-1983, alt.; music: Johann Löhner; 1645-1705, adapt.; text © Oxford University Press. All rights reserved. Used by permission under OneLicense # A-706920.