Seventh Sunday after Epiphany, Year C (2/24/2019)

Genesis 43:3-11, 15

Psalm 37:1-11, 39-40

1 Corinthians 15:35-38, 42-50

Luke 6:27-38

Click the play button to listen to this week’s sermon.

Is there any simpler command of Jesus than to love the enemy? Is there anything more seemingly impossible? Yet, is there anything more critical to the survival and thriving of human community?

The Prayer of the Day for today is based on the famous prayer attributed to Saint Francis of Assisi:

Lord, make me an instrument of your peace.

Where there is hatred, let me sow love.

where there is injury, pardon;

where there is doubt, faith;

where there is despair, hope;

where there is shadow, light;

and where there is sadness, joy.

O Divine Master, grant that I may not so much

seek to be consoled as to console;

to be understood, as to understand;

to be loved, as to love;

for it is in giving that we receive,

it is in pardoning that we are pardoned,

and it is in dying that we are born to eternal life.

There’s a good chance that you’ve heard the prayer of Saint Francis before – Lord, make me an instrument of your peace. But, have you heard the story of his courageous experiment in peacemaking?

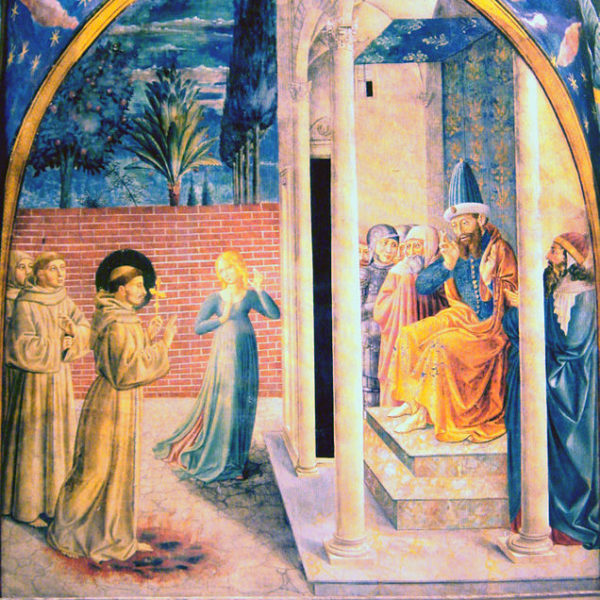

Eight hundred years ago this year, during the Fifth Crusade, Francis crossed the battle lines in Damietta, Egypt, to meet with Sultan Malik al-Kamil. A great deal of legend has sprung up around this event, and it’s impossible to determine the exact nature of their encounter. Still, what we can know sheds light on how truly remarkable it was. Paul Moses, author of The Sultan and the Saint, makes the following observations:

“I think one has to be careful about taking events from the distant past and applying them to the present, but I do see a lot of value in holding up Sultan al-Kamil as a model for Muslims and Francis for Christians. We know from the historical evidence that they managed to be courteous and friendly under terrible conditions. Francis never demonized Muslims in the way that was common in the Christian world at that time. He disarmed his rhetoric. And the sultan was known for his goodness to Egypt’s Christians….

[What’s more,] not only did he welcome Francis, but he also showed a generosity to the defeated Crusade army that shocked its leaders, who believed he had to be a Christian in secret. The truth is that his treatment of Francis and his vanquished enemy came straight out of Islamic teachings, which the sultan, a nephew of Saladin, knew well.”[1]

In a medieval context of deep-seated religious hostility, the meeting between Saint Francis and Sultan al-Kamil was a sort of miracle. It must have required profound wisdom and self-discipline on the part of both figures, whose encounter, although it did not succeed in bringing the conflict to an end, at the very least demonstrated the possibility of peaceful relations between the Muslim and Christian worlds. It was an exercise in loving the enemy.

Is there any simpler command of Jesus than to love the enemy? Is there anything more seemingly impossible? Enemies, after all, are identified in the first place by the factors that convince us to oppose them, and it’s counterintuitive to love that which we oppose. This is especially true when the conflict is reinforced by violence, and the pain and grief that come as a result.

The love of enemy has long been ignored as an impossible ideal. And for that reason, it’s rarely tried. Of course, this kind of love requires that we forfeit the gratification that comes from judging, resenting, antagonizing the other. Righteous indignation makes us feel strong, and it’s an incredibly vulnerable thing to approach the enemy from a different stance. But, that’s precisely the power of love. To love my enemy is to refuse to allow him to dictate the terms of our interaction; it is to “not be provoked by evildoers,” to borrow language from our Psalm today, but to provoke a new and unexpected dynamic.

Like Saint Francis, Saint Martin Luther King was practiced in loving his enemies. He published a now-famous sermon on the subject, the wisdom of which I can’t surpass with my own words:

“Probably no admonition of Jesus has been more difficult to follow than the command to ‘love your enemies.’ Some men [sic] have sincerely felt that its actual practice is not possible. It is easy, they say, to love those who love you, but how can one love those who openly and insidiously seek to defeat you? Others, like the philosopher Nietzsche, contend that Jesus’ exhortation to love one’s enemies is testimony to the fact that the Christian ethic is designed for the weak and the cowardly, and not for the strong and courageous. Jesus, they say, was an impractical idealist.

In spite of these insistent questions and persistent objections, this command of Jesus challenges us with new urgency. Upheaval after upheaval has reminded us that modern man is traveling along a road called hate, in a journey that will bring us to destruction and damnation. Far from being the pious injunction of a utopian dreamer, the command to love one’s enemy is an absolute necessity for our survival. Love even for enemies is the key to the solution of the problems of our world. Jesus is not an impractical idealist: he is the practical realist.

I am certain that Jesus understood the difficulty inherent in the act of loving one’s enemy. He never joined the ranks of those who talk glibly of the easiness of the moral life. He realized that every genuine expression of love grows out of a consistent and total surrender to God. So when Jesus said ‘Love your enemy,’ he was not unmindful of its stringent qualities. Yet he meant every word of it. Our responsibility as Christians is to discover the meaning of this command and seek passionately to live it out in our daily lives.”[2]

Is there any simpler command of Jesus than to love the enemy? Is there anything more seemingly impossible? Yet, is there anything more critical to the survival and thriving of human community? Dear church, to love the enemy doesn’t mean to acquiesce to him. On the contrary, to love the enemy is to preserve the possibility of his redemption, his transformation, even as it preserves the possibility of yours.

After all, Jesus accomplishes God’s redemption in this very way: “Father, forgive them; for they do not know what they are doing.”[3] Met with curses, he responds with blessing. Crucified by hate, he is raised in love. And, that love is the wellspring of our own courageous love – our own wisdom and self-discipline – in the face of opposition, no matter how hopeless the circumstances may seem.

[1] “What St. Francis & the Sultan Knew Well,” https://www.commonwealmagazine.org/what-st-francis-sultan-knew-well.

[2] “Loving your enemies,” Strength to Love, 49-50.

[3] Luke 23:34.